Leading through advocacy, education, and relationships

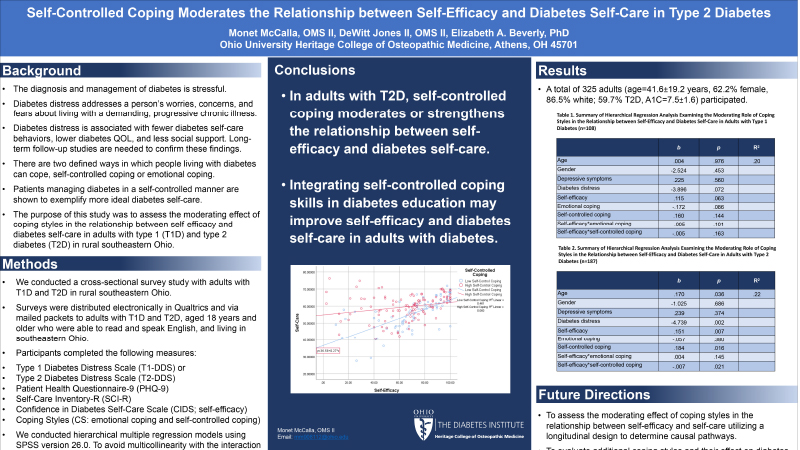

Self-Controlled Coping Moderates the Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Diabetes Self-Care in Type 2 Diabetes

Category: 2020

Author: Monet McCalla

Institution Affiliation: Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine

Self-Controlled Coping Moderates the Relationship between Self-Efficacy and Diabetes Self-Care in Type 2 Diabetes Monet McCalla, OMS II, DeWitt Jones II, OMSII, Elizabeth A. Beverly, PhD Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, OH 45701 Introduction: The diagnosis and management of diabetes can be very stressful. Diabetes distress refers to the negative emotional experience of living with diabetes. It addresses a person’s worries, concerns, and fears about living with a demanding, progressive chronic illness. Self-efficacy and diabetes self-care are heavily affected by the emotional hardships associated with diabetes, consequently, coping mechanisms are critical in management. There are two defined ways in which people living with diabetes can cope, self-controlled coping or emotional coping. Patients managing diabetes in a self-controlled manner are shown to exemplify more ideal diabetes self-care. Objective: The purpose of this study was to assess the moderating effect of coping styles in the relationship between self-efficacy and diabetes self-care in adults with type 1 (T1D) and type 2 (T2D) diabetes. Methods: Participants completed the Diabetes Distress Scale for T2D or T1D, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, the Confidence in Diabetes Self-Care Scale, Coping Styles, and the Self-Care Inventory-Revised. We conducted hierarchical multiple regression models using SPSS version 26.0. Results: A total of 325 adults (age=41.6±19.2 years, 62.2% female, 86.5% white; 59.7% T2D, A1C=7.5±1.6%; duration=12.4±9.6 years) participated. Mean scores for self-efficacy (t= -.892, p=.373), emotional coping (t=0.499, p=.618), and self-controlled coping (t=.925, p=.356) did not differ by type of diabetes. In the T1D model, the interaction between self-efficacy and emotional coping (b= -.005, p=.101) and the interaction between self-efficacy and self-controlled coping were not statistically significant (b= -.005, p=.163). In the T2D model, the interaction between self-efficacy and emotional coping was not significant (b= .003, p=.145). However, the interaction between self-efficacy and self-controlled coping was statistically significant (b= -.007, p=.021), indicating that self-controlled coping moderated the relationship between self-efficacy and diabetes self-care in adults with T2D (R2Δ=0.03, p=0.046). Conclusion: Findings suggest that self-controlled coping moderated or strengthened the relationship between self-efficacy and diabetes self-care in adults with T2D, such that more self-controlled coping was associated with higher levels of self-efficacy and more self-care behaviors. This work is ongoing and future plans include incorporating problem-solving and self-controlled coping skills in diabetes education programs in rural southeastern Ohio.

Watch Video

Phone: 567-712-0697

Phone: 567-712-0697